On "Void Stranger"

#18 - Void Stranger

The following will contain light spoilers for what you might consider “Act 1” of the video game Void Stranger—roughly the first 5-10 hours of play. Nothing I say here would “ruin” it, I don’t think, but if the description on itch.io or Steam appeals to you, I’d consider playing it; and if you do decide to play it, I really do recommend playing it knowing as little as possible. I will also mention here that I have put 45 hours into it but have not finished it, so I guess it’s possible that what I will write here will be somehow negated by the final act? I doubt it, but maybe worth mentioning.

I will also mention that I got it because I was so intrigued by System Erasure’s equally excellent and surprising shoot-em-up, ZeroRanger, which I played as part of itch.io’s ludicrously inexpensive Palestine Relief Bundle. This bundle also has a bunch of other stuff I’ve heard is good, like A Short Hike and Coffee Talk, and a bunch of stuff I haven’t heard anything about but I’m sure is also really good, all for like $8 minimum or something. I recommend it! So there you go. Bye!

There is a sense in which the psyche, or at least my psyche, sometimes feels like a series of puzzles. Taken on an instance-by-instance basis, these puzzles are often fairly straightforward: I’m more upset than I think I should be because this reminds me of something in my past; I’m actually worried about y, even though it feels like I’m worried about x. These puzzles are discrete and, even if I can’t actually solve them, I can untighten the screw a bit through understanding them: oh, so that’s why I feel bad.

But these manifestations are secondary, epiphenomenal. Selfhood, I think, also encodes a deeper, darker mystery, one I can’t even formulate the terms for. That we experience anything at all is a strange and haunting thing; how much stranger and more haunting that this experience is so malleable, contingent, and incomprehensible. We are bound to histories and bodies, wants and needs, that we did not choose and can barely understand. It’s all pretty weird.

This strangeness stays, for the most part, at the margins of conscious experience. Grief and illness draw the weird independence of the body to the fore; reactionary politics and conspiracy theories weaponize the frightening unknown towards repressive ends; religion renders the cosmic approachable and communal through systems of ritual; trauma encodes and reiterates the literally nightmarish dimension of both personal and shared histories; art often attempts to articulate these strangenesses in a way we can wrestle with more actively. Still, the fact that things are elementally weird—often in a way that’s, well, kind of scary—doesn’t have anything to do with most of the tasks that make up most of our days unless we’re paying a particular kind of attention, and even then it tends to slip from view.

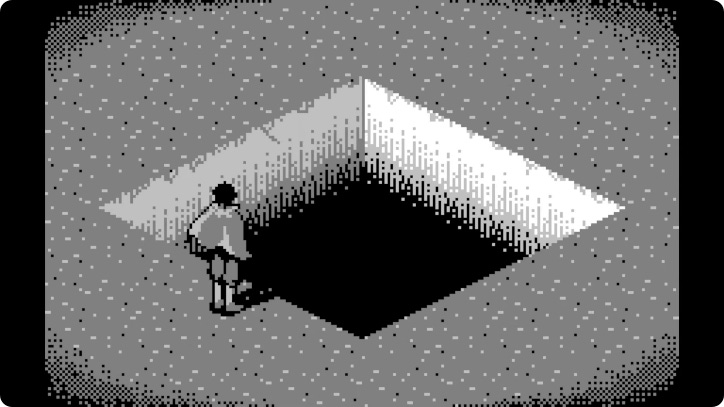

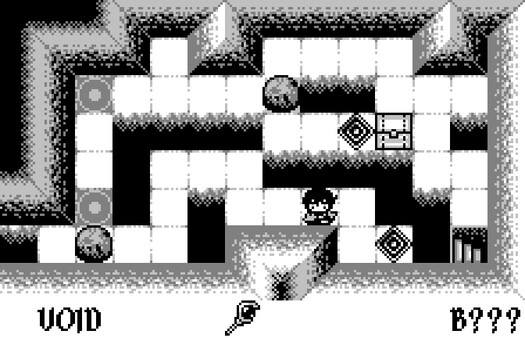

Void Stranger is a puzzle game. You control a character known as Grey. She appears to you primarily as a squished, low-detail Game Boy-style sprite, though she also is given a few wonderful pixel portraits. After a short, cryptic cutscene, you are dumped into a dungeon; when you go down the stairs and open a box, you receive a strange rod that allows you to lift and move floor tiles, one at a time. This is the main way you interact with the game: lift, move; lift, move.

But, as the game tells you in its first moments, “something is wrong.”

One classic way of aesthetically treating the Weirdness of Things is what we call “Lovecraftian” horror. This refers, I think, to a particular figurative sensibility: a way of narratively and imagistically encoding existential dread. Non-Euclidean architecture; squidly nightmare gods under the sea; books that contain things we oughtn’t learn—this is the vocabulary of Lovecraftian horror, and it has proven surprisingly enduring. (As is always worth noting, Lovecraft was also a fellow who was at least as scared of miscegenation as he was of the cosmic void; whether his figurative vocabulary is inextricable from his racism is a very good question.)

The vibes of Void Stranger definitely tend at times towards the eldritch: the visual aesthetics in particular sometimes resonate with this tradition. But Lovecraft’s fiction in particular usually takes ultimate recourse to the unspeakable—to negative space. A story will build to a point that words can’t capture, and then the story will say that words can’t capture them, and then the narrator entrusts his manuscript to an unfortunate assistant and goes to live in a hospital or something. The momentum of the stories often lend weight to these climactic, apophatic epiphanies, but the stories are wrought more in shadow than in anything explicit.

The unknowable in Void Stranger, on the other hand, is a constant, inescapable presence, a frightening light shining through the cracks. Weird stuff is everywhere. Why did I have to enter a 6x6 tile “brand” at the beginning of the game? Why do I have a magic Sokoban rod, and why does it make me feel so bad? Why does every treasure chest contain only a dead locust?

The first real formal joke of the game arrives when you hit a resting point. “This seems like a nice place to rest,” it says. If you choose to rest, the game just…quits. As in, it actually kicks you back to your desktop. You have to go back and boot it up again. (I can’t, off the top of my head, recall another game which does this—maybe Doki Doki Literature Club? which I haven’t played—though NieR: Automata’s joke endings come close to the same feeling.) When you do start it back up, you are instantly greeted with an out-of-context…vision? Flashback? Tricks like this, equal parts frightening and funny, are everywhere.

More than a few games perform this kind of metafictional fucking-around, and I do think the medium wears that tendency pretty well; conceits that might come across as silly in film or books can often hit harder in a game. Still, this register only really works for me when it’s deployed in service of something bigger. It’s undeniably mechanically thrilling to “break the rules” in The Stanley Parable, for example, and I enjoyed the feeling that the game had anticipated the stupid bullshit I was trying to do; ultimately, however, I didn’t exit the game with a positive impression, because I found its philosophizing perfunctory and hollow. Are video games art? Buddy, a toilet is art. Did you know you are not acting freely, but are playing a video game that someone made? Yes, because I bought it on Steam, a service for distributing video games. (Some of this is just my bias against the question of determinism as it’s usually formulated, which seems to have no bearing on the very real experiential problem of agency: getting out of bed, etc. But whatever.) These are thought-provoking conceits; unfortunately, they provoke exactly one thought—“whoa, man”—and then terminate, satisfied.

Or, to take a less mechanics-focused example, I do not feel that Hotline Miami, a game I played this year and think is a genuine achievement, has anything interesting to say about violence as such. Do you like hurting other people? I do not. I don’t even play that many shooters, because they kind of gross me out. Moreover, while this is, tragically, a letter about a much cornier hobby than BDSM, if you do like hurting other people, it’s hardly the end of the world; I’m sure there’s someone in your area you could hit up for consent training or whatever.

In any case, one cool thing about video games is that they are not real. More to the point, I didn’t make Hotline Miami—you guys did! If you were actually worried, you could’ve made it about, like, laser tag. It’s a callous, insulting bait-and-switch: isn’t it fascinating, philosophically speaking, that you’re hitting yourself? (Luckily, Hotline Miami is not, whatever its creators might’ve thought, a game about the appeal of violence; it is, like the movie Oppenheimer, about the danger of becoming too deeply immersed in something you’re enjoying, and it conveys this quite well.)

NieR: Automata, on the other hand—the video game, alongside Dark Souls and Persona 5 Royal, which made me realize I love this stupid medium—is famously metafictional, but its trickery is all in service of its narrative, and that narrative is not merely about how wacky video games are, but is one of the most emotionally resonant science fiction stories I’ve ever experienced. (That said, it is indeed also a video game about how wacky video games are, but it treats this topic far more tenderly and intelligently, in my opinion, than the cynical dorm-room skepticism of The Stanley Parable.) It takes the conventions and limitations of video games and folds them into the story it is telling, achieving a kind of aesthetic integrity I sincerely hadn’t thought possible before playing it.

Void Stranger is firmly on the side of NieR, I’d say. It is a game which loves video games, and it wants to use them to show you something you haven’t seen before. It uses every available convention and mechanic to tell its story, the camera panning suddenly back to show that what you’ve been taking for granted is itself significant. It is a puzzle game all the way down, in every way it can be.

The plot, which is revealed masterfully and gradually, is well-crafted, haunting, surprising, and emotionally charged; at no point have I been disappointed. I confess, however, that as some of the pressure of unknowing has let up, my experience of it has gotten a bit less intense. (For now! I haven’t achieved the “true ending,” because about 45 hours in I was getting impatient and started looking stuff up, and then realized I didn’t want to actually “ruin” the game for myself that way. In any case, I have heard that the ending is superb, and I believe it.)

This is the way art like this usually goes, I think—which is itself sort of comforting. The confusion of the journey, fucked-up as it is, has a thrill and beauty that nearly any resolution can’t match. Frustrating aesthetically, maybe, but given how unresolved life tends to be, one hopes this might sometimes be the case. (The formalist outsider horror masterpiece Higurashi When They Cry, a visual novel I’ve wanted to address here but like too much to know how to write about, is perhaps the greatest exception I can think of to this principle.)

But especially in the thickest weeds of Void Stranger’s mystery—after I realized how deep the questions went, but before answers began to concretize—I felt like I was beholding an uncannily cutting representation of the darker side of psychic life. This is the feeling that Void Stranger captures: the feeling of doing the busy work that needs to be done, tending to our small garden of comprehensible, rational needs and wants, solving the silly little puzzles that make up our days—moving blocks from here to there, avoiding predictable-but-still-tricky obstructions—trying, and failing, not to feel that these are just small oases of necessary sense-making in a vast desert of bewildering hostility.

What is moving about the vision of the game, though, is that, for all its meticulous opacity and genuine difficulty, at no point does it feel genuinely impossible. Unlike a game like Baba is You, for example, where you really have to mentally grasp the solution to the puzzle before implementing it, if you’re stuck in Void Stranger you can often just kind of noodle around until something works. I’ve looked stuff up here and there, but in my experience with the game thus far, there has only been one truly opaque mechanic, though it makes sense in hindsight, and only one truly opaque puzzle, which I think might have gone a little overboard. (I looked up the solution but, hilariously, I’m genuinely not sure what solving it did.)

Art is founded on the rhythmic generation and satisfaction of desire: we want to see something new and beautiful; in the middle of a story, we want to know what happens; after the song is over, we want to hear it again. Many of Void Stranger’s more gnomic utterances concern hunger and need. I genuinely could not recount to you any of the contexts in which the phrase occurs, but Void Stranger repeats this mantra throughout: “We have no hope and yet we live in longing.”

But crucially, for all the grief and unfulfillment the game depicts, it’s a very fulfilling game to play. It’s really fun! It’s very difficult at times, but it’s really fun. If you like this kind of puzzle—and unfortunately you probably do, I think, have to like this kind of puzzle to enjoy the game—it will reward you, over and over again. The basic design is extremely solid. The floors of the dungeon are wonderfully paced: systematically introducing mechanics, bringing them to a head, cooling down, then dropping in strange, wonderful, well-timed narrative beats. NPCs drop hints that make no sense at first but wind up being clear and helpful when considered from the right angle. The more time you spend proceeding through the dungeon, the more generous the game becomes—the more tedious dimensions of navigating the dungeon get much easier surprisingly quickly. The story it unfurls is a deep, rich, satisfying one. The soundtrack is really good. There’s one song that sounds kind of like a poignant take on the “Underground Castle” theme from Soul Blazer, and both rule extremely hard.

Here, ultimately, is one story that Void Stranger tells. The world doesn’t make a lot of sense, but the work you do adds up. It is worth it to try. The developers (whose company is wonderfully named System Erasure) give the following “tips” in the storefront game description:

The game autosaves between each room, so take it easy

If a puzzle seems impossible, get some rest

If that doesn't help, try asking someone for help

Good luck!

Pretty good advice in general! Okay, see ya!

i didnt read past the first couple grafs cause I want to play this but a short hike is dummy cute and u can finish it in one sitting

Yay new post! VS and ZeroRanger are super fun. I like that the developers recreate the games that influenced that game within that game. I just saw Picassos 40+ riffs on Las Meninas and some were really complex and some were just squiggles. But I liked that even the abstract ones were recognizable, and that’s how I feel about SEs games, like it could be a menu or a boss from esprade and it speaks a lot about the love they have for the genre. And it’s not like winking or annoying like Stanley.

I think OneShot does the exit-game-on-save thing too, that was in a few itch bundles as well