Are games art? Scattered thoughts on a pretty dead question

#12 - Piss Christ, Duchamp, World of Warcraft, Jo Walton, etc.

Hello all! This whole thing has been kicking around my head ever since reading the section of Playing at the World I quote partway through the letter. It is, as my subject suggests, a bit all-over-the-place, but hopefully there’s something interesting in there for you. If not, well, more content will be coming your way shortly. Love content! Okay see ya!

The world contains a large quantity of strange and interesting things. Some of these things are made by people, and some are not; some of these things are made with particular ideas in mind, some of them are not. No matter their provenance, these things exist, all around us; much of life involves encountering them, engaging with them, talking about them.

In order to better perform these operations, people sort the things they encounter into mental groups: they generalize. These are all food; these are all blue; these are all pleasant; these are all trash.

The order of operations here, I think—first things, then groups—is helpful to remember, because a classic mistake people make is believing that the groups denote something as real as the things themselves. This is why I’m no fun when people ask shit like, “Is a hot dog a sandwich?” I know it’s a joke question. But what do you people want from me? Oh, let me contemplate the Platonic ideal of sandwich, which definitely exists, and then get back to you. I just don’t think that’s how language works. “Sandwich” is a word we deploy in specific situations to effect communication; it is a concept we have invented in order to do things. I don’t know if a hot dog is a sandwich, man; what I do know is that if you asked me for a sandwich and I brought you a hot dog, the likelihood that you’d be confused or irritated is higher than it would be if I brought you a PB&J. Does that mean a hot dog is only 70% of a sandwich? Angels on a goddamn pinhead, I tell you. (This is all party-pooper stuff, I know, but this is my newsletter, so it’s my party to poop.)

In any case, within the set of all the objects in the world, there exists a subset of objects that we refer to as art. What falls into this set shifts with the tides of political, institutional, and social contestation. Theodore Sturgeon’s father beat him for reading pulp science-fiction magazines; now Samuel R. Delany gives lectures on Theodore Sturgeon’s work at prestigious university English departments. Everyone freaked out at the premiere of the Rite of Spring: “This isn’t music,” they said, although they probably said it in French. The history of conceptual and performance art, fundamentally intertwined with the rise of the modern institution of the art museum, comprises probably the weirdest and richest set of experiments in this register. Getting shot is art. A banana stapled to the wall is art. Eating the banana...isn’t art?

It’s fun to point and laugh at this stuff—and it is definitely very, very funny—but these arguments are just a loftier variation on the same kind of dividing and classifying that people do every day, albeit a variation performed by major museum curators throwing Sackler family money around. Which leads me to my next point: if politics is fundamentally about the distribution of resources, which it is, then the question of what art is is indeed a terribly political one.

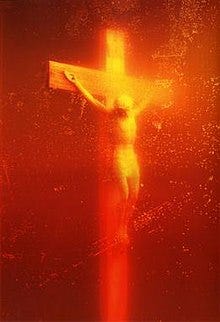

The highest-profile example of the last few decades is still probably the time the clowns in Congress used their philistinic misunderstanding of Andres Serrano’s stunning “Piss Christ” to defund the DEA. (Imposing brutalizing austerity measures in response to a genuinely profound aesthetic meditation on the Christian incarnation is, ultimately, a gesture perfectly emblematic of the ludicrous idolatry that is most of American Christianity. But I digress.)

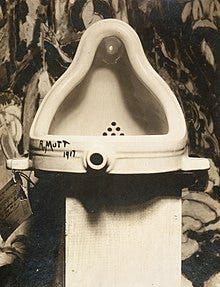

Of course, the most famous work of art in this genre is probably Michel Duchamp’s toilet. For those who don’t know, Duchamp put a god damn urinal in a museum and called it art. (Perhaps relevantly, at the end of his life Duchamp quit art to play chess all day, because he said chess was the highest art form—another point on the board for gamers.) Everyone freaked out and now the urinal is in art history textbooks across the world.

Now, I have no opinion on all of this, really, beyond thinking that it’s a pretty funny move to submit a toilet to an art exhibit. More to our point, the question comes up in Jon Peterson’s Playing at the World, a book which tracks the genealogy of tabletop role-playing games like Dungeons and Dragons.

There are enthusiasts anxious to elevate role-playing games to the status of an art form—while it is undoubtedly true that an artist could make art from a role-playing game, modern art has vividly demonstrated that an artist can also make art from a shovel, a bicycle tire or similarly mundane items. The importance of role-playing games does not lie in any artistic pretension so much as in their world-forging expansiveness, the sheer audacity of games in which an improvised table-top discussion conjures an epic world into being. It sounds absurd, even preposterous, yet it captured the imaginations of millions. Role-playing games are a testament to the curious ability of the human mind to embrace a bare sketch of a situation, to fill in its undefined areas and above all to believe it, to play at these worlds in such earnest that we lose ourselves in fictional personae.

I was really struck by this shift of emphasis. Perhaps because I’m slow on the uptake, I find it oddly liberating to consider the significance of a cultural object as totally detached from the question of whether it’s art, let alone whether it’s “good” art. Yeah, you can make art out of a game, but you can also make art out of a toilet. Whatever. A tabletop role-playing game’s legibility as an aesthetic experience isn’t what makes it valuable.

I brought up that art is a politically contested term because I don’t want to imply it isn’t important as a concept, or doesn’t have its place. I find it helpful to think of myself as an artist, for example, because it makes me feel slightly better about being thirty years old and living at my parents’ house. But beyond being totally over-determined, “art” is one of those words, like “entitled” or “pretentious,” that people often use to push each other around—to dismiss things without engaging more deeply. “How is that art,” said some AI guy about a Rothko painting, in a tweet I can’t be arsed to find. It feels to me like if we accept that guy’s terms, we’ve sort of lost already. You can argue, correctly, that non-figurative art is art, or you can, like, eat an edible and play ping-pong. Life is short and good, but it’s also long and stupid.

So let’s skip the question of what “art” is, for now, and talk instead about what it does. One strain of thinking about art, stretching from Horace to Zadie Smith, holds that it ought to improve us—it must, in the classic formulation, teach and delight.

I don’t really have beef with this definition. I like learning things! I like being delighted! It’s a good definition of art. It does a lot. I think about it sometimes.

Fundamentally, though, I’m not sure I know what it means to be improved, at least in terms of mass culture. Teaching is a marvelous thing—I’ve been a teacher for most of my adult life—but what is it we (all of us) need to learn? Mass culture takes as its audience, well, the masses, and teaching, as I understand it, is ideally a very personal thing, one which facilitates the student’s capacity to think things through and express what they want to express, with necessary reference to their particular goals and needs, always bound by the paradox that the student both knows best what they need and can’t yet know what they don’t know. What would it mean for mass culture to fill this role?

The most recent go around this merry-go-round that I, at least, paid attention to, was the one where everyone was talking about how the realistic novel teaches us empathy. Well, do realistic novels teach us empathy? I don’t know. Probably? Sometimes? I think I’m a more empathetic person because of the novels I’ve read. Still, I’ve met a lot of assholes who’ve read a lot of books, and a lot of nice people who haven’t read that many. I’m also not sure that empathy ought to be the highest aim, at least politically speaking.1 Relatedly, some people have claimed that video games make us better people. First of all, while I haven’t read the book, fucking lmao2; second of all, if that’s true, I genuinely cannot imagine what people who play video games would have been like without them.

Ultimately, I can’t say that I know what we all need. I sort of know what I need: fruits and vegetables, some (but not too much) socializing, sunlight, about eight hours of sleep, and a precisely-calibrated cocktail of psychiatric and hormonal medication. (Fitter, happier, more productive…) I guess I’d say everyone probably needs at least a couple of those things—but that’s about as far as my normative imagination takes me on this front. Food, shelter, water, access to healthcare, a life free of exploitation and immiseration: these are not wild asks. This is not an original appropriation (I think I saw Corey Robin say it first?) but Freud’s definition of the goal of analysis is basically my understanding of what socialism can do: transform hysterical misery into ordinary unhappiness.

Now, there’s definitely stuff we should learn as a society, but at this point it seems like what Americans need to learn is, like, that murdering people who unnerve you on the subway is bad, and I’m not sure a well-wrought novel about the ambivalences of social life in the metropole is going to teach the lesson that wanton murder is bad to anyone who doesn’t already know. Political solidarity sure would be good to learn, and I do think that art can hint at how solidarity might feel; still, I have a hunch that the way to really learn this is through collective action, not art. Besides, no matter how politically excellent your work is, people can take it however they want, and people, empirically, are wild as hell, capable of reading all sorts of crazy shit into otherwise ideologically salutary cultural objects. (Consider the red pill.)

Apologies if I’m beating the same old drum, flogging a dead horse, otherwise hitting something that oughtn’t be hit any longer—but I really do believe that the reason people are really awful to each other is not because they haven’t read enough novels, but because that we live in a world where the dominant mode of production incentivizes a small group of people to be variously, inventively, and totally awful to everyone else, and awfulness begets awfulness.

2

Back to art, though. What are the stakes of the question of whether a game is art? I am not saying I am above this concern. (As always, I’m largely projecting; like all my writing, this essay is based on the belief, which I usually do not actually feel but instead take on faith, that my own experience evinces something other than meaningless idiosyncrasy and half-assed windmill-tilting.) So let me be upfront: I, personally, was kind of a snob about this all for a while. In my case, I didn’t understand the point of games that weren’t narratively ambitious in an immediately legible way. The experience I desired was one that was recognizable in terms external to the medium.

Besides that, I liked the idea that games were art because I found it socially and existentially legitimating. Even as I bear an equally unfair knee-jerk reaction against games which seem designed to appeal to extrinsic criteria of “art,” the idea that video games still are art makes me feel better about fucking liking them so much. Since I was like, eleven years old, I have felt, often quite deeply, that I have wasted my life, missed my calling, etc.; this is a thought primally intertwined with video games, specifically World of Warcraft, an immense human achievement that should be illegal. (I’m joking, mostly.) Thinking that I’ve spent the last couple of years obsessed with an art form, not a children’s toy, makes me feel better about all the time I spent not reading Kant, or whatever the hell I think I should’ve been doing.

Concerns about projection aside, it’s not an especially audacious claim to say that I do not think I am unique in having disproportionate anxieties around questions of aesthetic consumption. But these neuroses are just that: neuroses, not thoughts which bear usefully on reality. I think it’s worth lingering on this. Why do so many people freak out about culture? Who cares?

On one Freudian definition of neurosis—there are several—neurosis is when the part of us Freud calls the ego, a word which should’ve been translated as the “I,” can’t maintain a given strategy of ineffectually and obsessively whacking the unruly and desiring id back into its shadowy hidey-hole; because of this failure, “ordinary” subjectivity breaks down, resulting in pathology and dysfunction. This happens because the chaos zone at the heart of the desiring subject has a direction all its own, and this is disconcerting.

On this interpretation, neurosis manifests when we cannot bear to want the things we want. I think this inner conflict—the strange and agonizing difficulty of wanting what you want: of avowing your own desires—is a big part of why so much weird shit comes out when people start talking about seemingly trivial cultural objects. Because it’s weird, at least to me, that movies and TV in particular are ground zero for so much bizarro culture-war nonsense. The right’s compulsions in this register are agonizingly obvious, but it’s also weird that left-leaning people insist that mass culture shaped and delivered by corporations has, or ought to have, the capacity to inspire revolutionary desire—as if the capacity of our class enemies to incorporate revolutionary ideology into their media commodities weren’t actually a deeply unhappy sign. It’s weird that people feel it’s imperative for schools to ban fiction about non-normative romantic relationships; moreover, it’s weird that the idea that children might be exposed to any representations of any kind of sexuality feels so apocalyptic to people. None of this makes sense to me without the belief that cultural objects are sites of inchoate, untold, truly massive desire.

To take the most obvious example of this desire, it’s a truism at this point that actors and musicians are capable of inspiring “sexual awakenings” (a really astonishing turn of phrase, honestly: are you born with your sexuality asleep? Where in us does sexuality sleep? Can it wake up too early? Can we ever fully wake it up? What else in us is sleeping?). But I think sexual desire is really just one manifestation of a far more wide and vague and powerful field of desires which culture can satisfy, a field of desires every bit as vexing and inscrutable and important as sexuality, if not more so.

These more mundane manifestations of this desire are almost hard to perceive, because they’re so taken for granted. Think of how far out of our ways we go to experience culture. People travel hours and pay hundreds of dollars to see concerts or eat exciting dinners. They lose sleep playing games, reading, watching movies and TV. It is impossible to actually conceive of the sums of capital circulating through the entertainment industry. None of this would be possible if people didn’t want—so, so badly—to experience art and media and culture.

There’s this immense, unspoken desire at the heart of American society—of every society, insofar as such generalizations are possible, which they of course aren’t. But consider the prevalence across times and societies of those expressions we lump under the heading of art or entertainment: music, acting, poetry. You don’t need to essentialize to observe that it’s extremely weird that people spend so much time doing stuff that doesn’t, in any obvious way, do anything.

I was writing before that I was worried that I was wasting my time on the wrong cultural objects: on, in (sorry) David Foster Wallace-ish terms, entertainment that isn’t art. Now, time can’t really be wasted; “waste” is a metaphor which emerges from an ethically dubious figurative imaginary, one which transforms every facet of reality into a discrete, quantifiable object, and then proceeds to sort all of reality into the categories of garbage and not-garbage. Actually, time is the medium of all subjective experience: it isn’t a “thing,” and our experience of it isn’t really quantifiable. We tell time in the form of numbers because then it’s easy to tell if we’re late for work.

But even if “wasted time” is a fake idea, we still choose (insofar as anyone ever chooses anything) to do one thing over another; this means there’s a value structure in place. You can say, meaningfully, that you prefer to do x over y—even if all that means is that you feel better after doing one thing than you do after doing another.

So what if games aren’t art? What happens then? What, actually, are the stakes? Why would the category I put something in convert it from being a “worthwhile” use of my time to a “waste” of my time? Am I just afraid that people might make fun of me for liking them? I have news, my friends: video games have won. Everyone plays them. They are everywhere. They are taught in universities. Let people make fun of them, if they so desire. It does not do to be a sore winner.

I’ll put my cards on the table. Here is a definition of “art” that I just made up: I think the word refers to expressive, intentional, formal objects, created by people. (Not all people are humans, but all humans are people; LLMs aren’t, but the humans using them are.) The “intention” can be a recontextualization, like Duchamp’s toilet; in any case, Duchamp’s toilet bore expressive content: it meant something different than a toilet in a bathroom means, and that meaning was aesthetic. (Even if you can’t paraphrase in words what an object is expressing in words—I’d say you actually never can—it can be expressive; even if all it is expressing is an emergent sense of beauty, it’s expressive.) Clothes are art because they mean something in excess of their functions, which are to keep you warm and allow you not to be arrested for not wearing clothes. Art can be made by a workshop, an ensemble, or an individual; the meaning can be discussed in relation to its author, as an expression of the society from which it emerged, or as an autonomous formal object. A disposable plastic cup as such isn’t art—it doesn’t express anything; it’s purely functional—but it can have art on it, or it can be made in a way that makes it art. (“Formal” is kind of redundant—show me an object that doesn’t have a form—but I threw it in because I think formal coherence is perhaps the defining characteristic of art.)

So of course video games are art. A Dungeons and Dragons campaign is art. A bumper sticker is art. Wheel of Fortune is art. I once pinned a scam letter allegedly offering me a job to my wall; this made it art. (I took it down when a friend kindly argued that its expressive content was perhaps not edifying to look at every day.)

If I’m saying anything, which I might not be, I guess I’m just saying that this definition is ultimately trivial. We live in a world of objects; in modern industrialized society, most of these objects are mass-produced. Many of us feel compelled, for whatever combination of reasons, to create more objects; some of these objects are food; some are novels; some are tables. The really remarkable thing about objects is that they can change your life—your inner life, no less: that improbable, shadowy, elusive, intangible, utterly fundamental feature of experience.

And so I don’t mean to reject the idea that art can improve you. I am the person I am because of art. (Whether this is an improvement on how I’d otherwise be is not for me to judge, though I guess I like to think so.) Honestly, I’m not really trying to reject anything. I think it’s good that all these arguments are bouncing around in the world. I’m just some goofus in North Carolina: I don’t know nothing. Let the discoursers discourse, I say.

It’s just worth considering, maybe, what we lose when we privilege the idea of “art,” just like we maybe lose something when we believe that the only good art is that which we can see teaches us something. The world is full of so many things.

In conclusion, here is a scene I think about a lot, from Jo Walton’s novel Among Others. (It comes about halfway through the book, if you’re worried about spoilers.) For context, the narrator’s identical twin died in an accident before the novel began; in this scene, the narrator, who was reading the Samuel Delany novel Babel 17 a few pages earlier, has just been reunited with her sister’s ghost, who is silently enjoining the narrator to join her in death. (This book is narrated by a science fiction fan in the 1970s UK, but also fairies are real; the fact that it excellently executes on this premise continues to surprise me.)

“Let go,” Glorfindel [her fairy guide and friend] said, almost in my ear, a whisper so warm it moved my hair.

I wasn’t holding her, except that I was. Our hands reached out and did not touch, but the connection between us was tangible. It glowed violet. It was the only thing with colour. It wasn’t visible normally, but if it had been for the last year it would have been trailing around me like a broken bridge. Now it was whole again, I was whole again, we were together. “Holding or dying,” he said in my ear, and I understood, he meant that I could hold her here and that would be bad, and I trusted him about that although I didn’t understand it, or I could go with her through that door to death. That would be suicide. But I couldn’t let her go. It had been so very hard without her all that time, such a rotten year. I’d always meant to die too, if dying was necessary.

“Half way,” Glorfindel said, and he didn’t mean I was half dead without her or that she was halfway through or any of that, he meant that I was halfway through Babel 17, and if I went on I would never find out how it came out.

There may be stranger reasons for being alive.

The entire material apparatus encasing art and culture, the vast sums of wealth circulating in the form of various aesthetic commodities, the play of cultural capital among various elites—these are real, yes, and they’re very bad. One of the reasons they are so bad is because they are are all parasitic on the elemental power Walton is describing here: namely, the impossible fact that someone can line up a bunch of words in a way that can make a stranger want not to die. Entertainment, culture, art, trash—whatever you call it, whether it’s a game or a hobby or a novel or a movie or a song—it is a truly remarkable feature of reality that this occurs. I want to act and think with fidelity to this phenomenon, which, I think, means taking things seriously where they’re at, not where I think they should be. I don’t understand all the implications of this position, but I think that’s the point.

There’s a lot of writing about this. For example, in her profound and profoundly disturbing Scenes of Subjection, Saidiya Hartman argues (among other things) that political strategies which relied on Americans’ need to empathize with suffering enslaved Black people through media like Uncle Tom’s Cabin actually impeded a more substantive political program, because it made white people’s capacity to empathize the condition and limit of Black emancipation.

I decided the joke was a bit too obtuse, but I originally linked to the Wikipedia page for the kind of ant called the "gamergate,” a male worker ant which has the capacity to mate, and which I learned existed today. Poor little guy!